Reported by SUVI 2023-07-19

“Shippers could now find their cargo on one mega-ship, operated by one mega-alliance, calling at just a few mega-ports, but with a delay – or at worst an accident – leading to ‘mega-consequences” – OlafMerk

Overview:

Prior to the pandemic, prominent industry experts TI (Transport Intelligence) predicted a 4.6% CAGR (Compound Annual Growth Rate) in worldwide maritime freight transportation from 2016 to 2020. This anticipation arose as a consequence of the numbers’ moderate but consistent rise from 2009 to 2016. At the same time, analysts identified a number of possible dangers to this expansion, including global trade, political instability in the United States and Europe, and China’s ongoing economic decline.

By geographic region, over 85% of the total global market was dominated by 3 major regions, namely Europe, Asia Pacific and North America. This proportional share would remain largely the same during the upcoming period. Asia-related trade lanes spreading to Europe, North America and vice versa, along with Intra-Asia lanes, are also the busiest routes for sea freight cargos.

In terms of market share, top 20 multi-national service providers constituted over 60% of the total market (top 3 players K&N, DHL, DB Schenker combined share was almost 20%). The remaining 40% of the pie was serviced by the many thousands of other small and medium freight forwarders.

Key protagonists in sea freight trends for lines and ports:

With that in mind, the “NEW NORMAL” for sea freight arised with its own developments and market trends. All of them combined then further resulted in higher, but more stable freight rates, together with an expectation of more predictable service levels.

- Industry consolidation – increases stability, reduces choice.

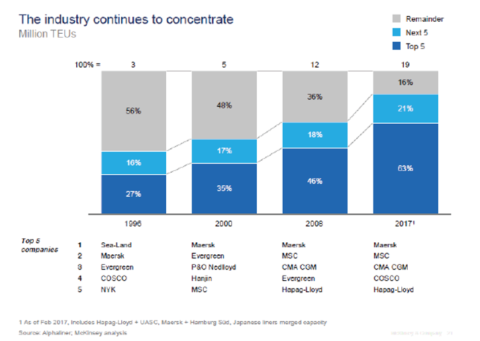

The industry continues to concentrate. The frenzy activity of merger and acquisition, or M&A in short, between major players in the industry has caused a significant structural shift in the carrier base and formed extremely competitive forces in container shipping.

Increased stability:

Joined forces are gradually reducing excess capacity, whilst there is also a steady but modest increase in container volumes, resulting in the market finally heading towards some equilibrium in the supply and demand equation.

This strengthens the position of the shipping lines, providing a pathway for many to return to profitability over the medium term – and empowering them to exercise more courage and discipline on pricing.

The good news for forwarders and shippers is that industry consolidation will reduce market volatility and enable a more stable environment for orchestrating ocean freight supply chains.

Reduced choice:

Such greater stability in the market, on the other hand, motivates container lines to raise their income levels by raising rates and decreasing options. It is because there aren’t many other large takeover prospects available, particularly in the Premier League.

- The new existence of mega vessels

Ultra-large container vessels (ULCVs) are massive boats that have grown in popularity in recent years. Despite their evident benefits and significance as a symbol of progress in the maritime sector, the ramifications for port and terminal owners must also be considered.

For starters, large container ships can only approach profitability if they are handled quickly and effectively within a port. When it arrives, large bursts of containers will be processed from a single giant vessel, which will arrive and depart all at once. As a result, tremendous strain is placed on ports and terminals, as well as on ground transportation access to and from the hinterland farther downstream.

CMA CGM Jules Verne container ship – the most infamous 16,000 TEU capacity ULCV

- Carrier alliances: sharing capacity & expertise

Like the mega-vessels and slow-steaming, carrier alliances are also here to stay.

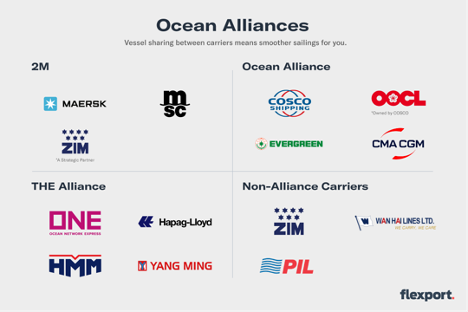

In response to different industry crises over the years, shipping lines have formed – and reformed – strategic partnerships to share capacity and experience. To mention a few, the THE, Ocean, and 2M alliances encompass practically all of the major shipping lines and so dominate 90% of trans-Pacific traffic and 96% of Asia-Europe trade.

- The 2M Alliance: Maersk and MSC.

In 2015, they agreed to a ten-year vessel-sharing arrangement on Transpacific, Transatlantic, and Asia-Europe routes. 2M has a strategic cooperation agreement with ZIM and used to have one with HMM, but in 2019, HMM moved to THE Alliance.

Additionally, MSC, Maersk, and ZIM also operate Transpacific and Transatlantic services outside of the alliance agreements.

- The Ocean Alliance: COSCO, OOCL, Evergreen and CMA.

COSCO acquired OOCL in 2018 after receiving antitrust and anti-monopoly approvals from China, the US, and Europe.

CMA and COSCO also have a number of non-alliance services on the Transpacific trade.

- The THE Alliance: Hapag-Lloyd, ONE, HMM, and YML.

This alliance is recently notable for bringing greater US Gulf port service on Transatlantic routes. All member East-West services are part of the alliance.

Vessel-sharing arrangements among these alliances have resulted in fewer port-to-port links and a significant drop in main channels. As more cargos concentrate in specific destinations, vessel rotations and terminal positions shift, putting increasing strain on ports and limiting shippers’ options.

- Pressure on ports:

This trend follows on from the previous one, as larger mega vessels enter service, causing medium-sized boats to cascade down into narrower trade lanes. The need for transformation in the port industry is greater than ever.

To begin, significant capital investments and redesigned port operations are required. Longer and stronger quays are needed at ports where giant vessels dock. The water level in the canal and harbor must also be raised to accommodate them as thousands of containers are lifted on and off the vessels. The port’s fixed assets are heavily utilized in such a short turnaround period, leaving it underutilized when no large vessels are present. Thus, there are greater peaks and valleys in operations, resulting in substantially less flexibility for container ports.

Furthermore, more yard area, handling equipment, larger gates, and more staff are required to handle the increased container volumes. All of this adds to the operational expenditure.

Outside of the port, congestion occurs, further delaying passage through the port into road or rail transportation networks. Overcrowding both inside and outside will make it difficult to access multi-modal ground links into the hinterland. This might add one or two days to the supply chain if goods are delayed on their way to their final destination in a warehouse, factory line, or retail store. The implications for lead times, inventory levels, working capital, and customer satisfaction do not end there.